After the chairman of the FA blamed the number of foreign players in the Premier League for ruining the national side, James Dutton asks why prejudiced and selective memories still course through English football’s memory…

“ARGH! Damn those pesky foreign footballers, they keep coming over here taking away our homegrown players! ARGH! I just wish they’d stop!”

“ARGH! We created this insatiable commercial cash-cow of a league and they all come over here wanting a piece of it! ARGH! It’s just not fair anymore!”

“ARGH! Just look at how many more home based players there were back in 1992. How things were better in 1992. HUMPH!””

“THEY TOOK OUR JOB!”

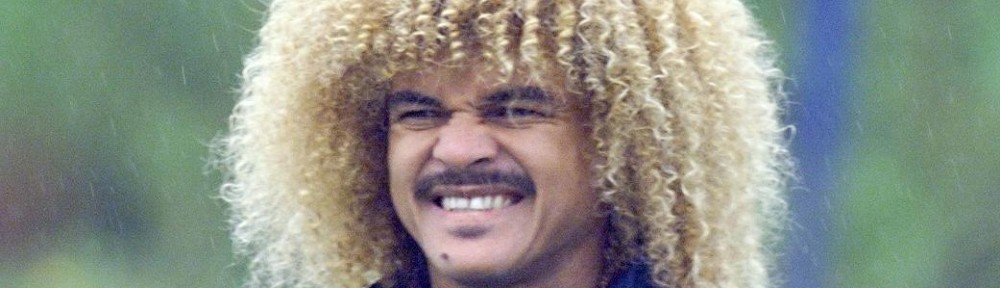

How incredibly short-sighted of me to forget England’s barnstorming success en route to qualifying for World Cup ’94, and boy we really showed those yanks in the searing heat that summer. The class of ’92 – the 69% as we know them – oh how we idolise them still. Des Walker. Andy Sinton. Micky Quinn. Dean Holdsworth. Mark Walters. John Scales. Carlton Palmer. Gods amongst men.

And even before that (what before 1992? Yes, even before 1992) wow, that 26-year golden age after the glory of ’66 when we qualified for two out of seven major international tournaments between 1970 and 1984. I mean they were just the best. Before the dark times. Before the foreigners.*

Why does everyone have selective memories when referencing the fortunes of the national side since the turn of the century, that overlook how consistently average England have been at football since the dawn of time? The proliferation of foreign talent in the Premier League is a popular smokescreen, an easy and obvious target.

Many gripe with the gross abundance of mediocre foreign talent, but that probably has something to do with the interminable problem of overpriced English talent. Jordan Henderson may be the most improved English midfielder in the division, but he will be forever dogged by that absurdly extortionate price tag of £16m for a 20-year old with one international cap.

There obviously is an argument about the decline in home-grown footballers playing in England’s leading league being detrimental to the fortunes of the national set-up. But this divine belief that the two are intrinsically linked is daft; the one-defining factor in years and years of moribund failure. We’re fixated by the wrong argument.

Standards have improved. Technique, touch and tactical awareness are now paramount to English youngsters – Henderson, Jack Wilshere and Phil Jones for instance – breaking into their club’s first eleven; by making them work harder to attain their goals it is undoubtedly improving them as footballers. Though to some this would be a deterrent because there are those who would suffocate under the challenge, this surely acts to differentiate the weak from the headstrong.

It’s a failure to accept responsibility, and reminiscent of a popular adage that penalty shoot outs are a lottery, rather than one of the ultimate tests of skill and nerve.

Since the advent of the Premier League and the drop-off of English talent, the national side has paradoxically out-performed every era that preceded it. Successive World Cup quarter-final appearances are almost unprecedented in the history of the English national team, no matter how much you believe the ‘Golden Generation’ underperformed.

What does it say about a nation whose reaction to being humbled 4-1 at a World Cup by their arch-rivals is to demand the worldwide installation of a multi-million pound instant replay system to avoid it ever happening again?

The constant referencing to landmark moments – 1966, Italia ’90, 4-1 against Holland at Euro ’96 and the 5-1 against Germany in 2001 – is as depressing as it is unheplful.

What Greg Dyke and his “Rivers of Blood” moment concealed is that there are far more damaging problems to the future of English football than the foreign talent which sells television deals. The constant misuse of the youth systems, right the way from U17 to U21 level; a trigger-happy approach which prematurely promotes footballers with limited experience of tournament football is far more corrosive for its long-term health.

Only until the arrogant attitude of instant gratification desists will the national side begin to progress, rather than wallow in habitual mediocrity.

* Yes I accept that these were 16-24 team tournaments, and by virtue of that fact more difficult to qualify for, but West Germany, Italy and Netherlands had few problems at the time.